Bacteria – yes, bacteria – could be the key to recycling EV batteries

There are more than 1.4 billion cars in the world today, and that number could double by 2036 . If all those cars burn petrol or diesel, the climate consequences will be dire. Electric cars emit fewer air pollutants and if they’re powered by renewable energy, driving one wouldn’t add to the greenhouse gases warming Earth’s atmosphere.

But producing so many electric vehicles (often abbreviated to EVs) in a decade would cause a surge in demand for metals like lithium, cobalt, nickel and manganese. These metals are essential for making EV batteries, but they’re not found everywhere . Most of the world’s lithium lies under the Atacama Desert in South America, where mining threatens local people and ecosystems.

Leading manufacturers of EVs need to keep import costs low and find a reliable source of these raw materials. Mining the deep sea is one option, but it could also damage habitats and endanger wildlife. At the same time, waste electronics filled with precious metals are piling up in landfills and in some of the world’s poorest regions – with 2.5 million tonnes added to the total each year.

EV batteries themselves only have a shelf life of eight to ten years. Lithium-ion batteries are currently recycled at a meagre rate of less than 5% in the EU. Instead of mining new sources of these metals, why not reuse what’s already out there?

The recycling economy

The largest lithium-ion battery recyclers are based in China . While recycling is often treated as an obligation that companies should be paid to do in North America and Europe, competition is so intense for dead batteries in China that recyclers are willing to pay to get their hands on them.

Most of the batteries that do get recycled are melted and their metals extracted. This is often done in large commercial facilities which use lots of energy and so emit lots of carbon. These plants are expensive to build and operate, and require sophisticated equipment to treat the harmful emissions generated by the smelting process. Despite the high costs, these plants rarely recover all valuable battery materials.

The value of the global market for metal recycling is expected to grow from US$52 billion (£37 billion) in 2020 to US$76 billion by 2025 . Without less energy-intensive recycling methods, this emerging industry will only exacerbate environmental problems. But there is a natural process for extracting precious metals from waste that’s been used for decades.

Bugs for batteries

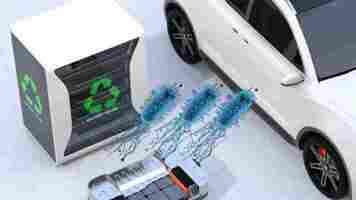

Bioleaching, also called biomining, employs microbes which can oxidise metal as part of their metabolism. It has been widely used in the mining industry, where microorganisms are used to extract valuable metals from ores. More recently, this technique has been used to clean up and recover materials from electronic waste, particularly the printed circuit boards of computers, solar panels, contaminated water and even uranium dumps .

My colleagues and I in the Bioleaching Research Group at Coventry University have found that all metals present in EV batteries can be recovered using bioleaching. Bacteria like Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans and other non-toxic species target and recover the metals individually without the need for high temperatures or toxic chemicals. These purified metals constitute chemical elements, and so can be recycled indefinitely into multiple supply chains.

Scaling up bioleaching involves growing bacteria in incubators at 37°C, often using carbon dioxide. Not a lot of energy is needed, so the process has a much smaller carbon footprint than typical recycling plants, while also contributing less pollution. While reducing EV battery waste, bioleaching facilities mean manufacturers can recover these precious metals locally, and rely less on the few producer countries.

Academics working on bioleaching to stop once they’ve removed all the precious metals from the electronic waste and they’re floating in solution. This is not enough for industry. We combine bioleaching with electro-chemical methods that can fish out these metals and make them useful for supply chains. Unfortunately, existing methods in metal recycling which involve lots of energy and toxic chemicals have been used for decades. Industries can’t always afford to innovate, so it’s up to the government to mandate changes and invest in cleaner alternatives.

EV batteries are a technology still in their infancy. The reuse of their components should be considered as part of their design. Rather than remaining an afterthought, recycling can become both the beginning and end of an EV battery’s life cycle with bioleaching, producing high-quality raw materials for new batteries at low environmental cost.

Most of the batteries that do get recycled are melted and their metals extracted. This is often done in large commercial facilities which use lots of energy and so emit lots of carbon. These plants are expensive to build and operate, and require sophisticated equip

This article by Sebastien Farnaud , Professor of Bio-innovation and Enterprise, Coventry University , is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article .

What the UK’s ruling against Uber means for the gig economy

It’s been a long old journey for former Uber drivers James Farrar and Yasseen Aslam. But after a five-year legal battle, the pair arrived at their chosen destination – a court ruling that drivers for the taxi app firm should be treated as workers rather than independent contractors.

It is a distinction that could have significant implications for the earning rights of Uber drivers, at a potentially heavy cost to the firm, which is fighting similar challenges around the world. The ruling could also have a marked effect on the wider gig economy, paving the way for similar claims that could come from online tutors, supply teachers, or freelancers.

Future cases are likely to test how far the February 2021 judgment stretches. But the court ruling certainly strengthens the message – from both academia and an official 2017 review of modern working practices – to other online platforms in the gig economy that the “misclassification” of their workforce will not be tolerated. For example, the judgment may encourage Deliveroo riders who were previously unsuccessful at asserting their employment status in court.

The Uber case began when Aslam, Farrar, and their fellow claimants successfully took on the firm in an employment tribunal in 2016, contending they were workers and therefore entitled to a minimum wage and paid leave.

Uber lost a string of subsequent appeals, culminating in the latest unanimous judgment against them by the UK’s Supreme Court. Giving the judgment , Lord Leggatt held that the original employment tribunal was correct for five key reasons:

Drivers have no say over their fares

A standardized written agreement is essentially imposed on drivers

Uber exercises a significant amount of control over drivers, including penalizing those whose acceptance rate falls below

Uber’s expectations

Uber dictates the way in which drivers should deliver their service and uses a rating system to manage this

Communication between passengers and drivers is restricted by Uber (preventing the formation of any future relationship between the driver and the passenger).

The balance of power

In short, the Supreme Court believed the drivers were subordinate to Uber, leading to an imbalance of power. Beyond increasing the hours spent working via the platform, drivers had no means of improving their economic position through entrepreneurship – something which could reasonably be expected of an independent contractor.

The judgment was welcomed by Farrar and Aslam, who told the BBC they were “thrilled and relieved” by the ruling.

Farrar added: “This is a win-win for drivers, passengers, and cities. It means Uber now has the correct economic incentives not to oversupply the market with too many vehicles and too many drivers. The upshot of that oversupply has been poverty, pollution, and congestion.”

For its part, an Uber spokesman said : “We respect the court’s decision which focused on a small number of drivers who used the Uber app in 2016. Since then, we have made some significant changes to our business, guided by drivers every step of the way. These include giving even more control over how they earn and providing new protections like free insurance in case of sickness or injury.

He went on: “We are committed to doing more and will now consult with every active driver across the UK to understand the changes they want to see.”

Whatever changes lie ahead, the landmark judgment is indeed a major step in tackling how vast numbers of working people are treated, with the potential to change the shape of the gig economy as we know it.

But it is worth noting that this judgment has been five years in the making. What is that compared to the speed at which online platforms like Uber can update its terms and conditions or business models?

It seems as though the law has engaged in a game of cat and mouse in attempting to hold platforms accountable for the way they treat their workforce. It may be that a future legislative response at the government level will be required to level the playing field for workers who may otherwise feel bound by the terms of their agreements.

For now, drivers have found a rare moment of certainty in the ever-changing gig economy. But while the drivers have won this battle, the question remains over who will win the war. We might be in for a bumpy ride.

This article by Jessica Gracie , PhD Candidate, York Law School, University of York is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article .

SHIFT is brought to you by Polestar. It’s time to accelerate the shift to sustainable mobility. That is why Polestar combines electric driving with cutting-edge design and thrilling performance. Find out how .

Tesla is removing radar from Autopilot, and it makes absolutely no sense

Forget about radar for self-driving tech . Tesla announced yesterday that it’s officially transitioning to its camera-based autonomous driving system, known as Tesla Vision.

Starting this month, Model 3 and Model Y vehicles, which will be delivered to the North American market, will be the first cars to ditch radar entirely, and employ camera vision and neural net processing for the performance of “Autopilot, Full-Self Driving, and certain active safety features.”

Naturally, one wonders why on earth would Tesla make such a change. And when Elon Musk twitted the launch of “pure vision Autopilot,” there were several comments expressing the same question.

In fact, it makes no sense to skip radar and rely solely on cameras.

Cameras may offer higher resolutions and lower production cost, but they have significant limitations. They are less effective in bad weather conditions and have lower accuracy during nighttime. Most notably, the neural networks that determine what is being seen by the cameras require large amounts of training and processing power – and both of these factors are intrinsically limited within a car’s computer system.

On the other hand, radar sensors are much more reliable as they offer better range and higher accuracy in terms of object distance and speed – no matter the weather or light conditions. They do have lower resolution, however, which means that they require tech enabling them to run at higher frequencies, and that’s costly.

To put it in a nutshell, the transition to cameras reduces cost which seems to be a larger trend for Tesla . Nevertheless, it’s impossible to comprehend how a camera could offer the same level of safety radar provides, which raises serious vehicle and road safety concerns. The excellent thread by Ed Niedermeyer in the tweet below is illuminative:

To make matters worse, Tesla warns that its Vision system will probably cause temporary limitations to some features.

What’s more, customers don’t really have a choice regarding the radar or camera system of their prospective vehicles. Those who ordered a car before May 2021 and are matched to a model with Tesla Vision will be notified of the change through their Tesla accounts prior to delivery.

Whether this switch will be successful for Tesla is highly doubtful. Let’s hope that it doesn’t result in any negative impacts on vehicle safety. Nobody wants that.

Do EVs excite your electrons? Do ebikes get your wheels spinning? Do self-driving cars get you all charged up?

Then you need the weekly SHIFT newsletter in your life. Click here to sign up .