How politicians manipulate the masses with simple AI

We’re three and a half years away from electing another president here in the US, but it’s never to early too prepare ourselves for the impending crapshow that is US politics.

The good news is, going forward, you won’t have to think so much. The age of data-based politics is coming to a close thanks to the innovations created by the 2016 Donald Trump campaign and the counteracting tactics employed by the Biden team in 2020.

Data used to be the most important commodity in politics. When Trump won in 2016, it wasn’t on the strength of his platform (he didn’t have one). It was on the strength of his data gathering and ad-targeting.

But that strategy was proven ineffective when it went up against the Biden team who, unlike Hillary Clinton’s campaign, conducted effective counter-messaging across the social media spectrum.

Data-based politics result in politicians gathering information on us against our will or knowledge. They then exploit that information to figure out what messages are likely to get people fired up.

Given an issue we’re not sure about, humans are likely to believe anything for a few moments, as long as it comes from a trusted source. And this is especially true when it comes to AI

A duo of researchers from Drexel University and Worcester Polytechnic Institute recently published a study demonstrating how easily humans trust machines and each other. The results are a bit scary when you view them through the lens of political and corporate manipulation.

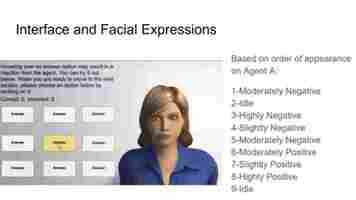

Let’s start with the study . The researchers asked groups of people to answer multiple choice questions with help of an an AI avatar. The avatar was given a human visage and animated to either nod and smile or to frown and shake its head. In this way, the AI could indicate “yes” and “no” with either mild or strong sentiment.

When users hovered their mouse over an answer, the AI would either shake its head, nod, or remain idle. Users were then asked to evaluate whether the AI was helping them or hindering them.

One group worked exclusively with a bot that was always right. Another group worked with a bot that was always trying to mislead them, and a third group worked with a mix of the two.

The results were astounding. People tend to to trust the AI implicitly at first no matter what the questions are, but they lose that trust quickly when they find out the AI was wrong.

Per Reza Moradinezhad, one of the scientists responsible for the study, in a press release :

Traditionally, what this means, is that it’s smarter to find people who look trustworthy than it is to find trustworthy people. And, what does trustworthy look like?

It depends on your target audience. A Google search for “woman news anchor” makes it clear that the media has a strong bias:

And you need only glance at Congress , which is about 77 percent white and male, to understand what “trust” looks like to US voters.

Even entertainment media is dominated by trust concerns. If you perform a Google search for “male video game protagonist” you realize that “scruffy, 30s, white guy” is who gamers trust to entertain them:

Marketing teams and corporations know this. Before it was considered an illegal hiring practice, US businesses often considered it company policy to only hire “attractive women” for customer service, secretarial, and receptionist duties.

In the wake of the 2016 elections, social media companies reevaluated how they allow data to be used and manipulated on their platforms. This, arguably, hasn’t amounted to any meaningful changes, but luckily for social media platforms the calculus behind society’s problems has changed.

Our data’s out there now. As individuals we like to think we’re more careful with what we share and how we allow our data to be used, but the fact of the matter is that big tech has been able to extract so much data from us in the past two decades that our new “normal” is a data bonanza for corporate and political entities.

The next step is for politicians to figure out how to exploit our trust as easily as they can exploit our data. And that’s a great problem for artificial intelligence.

Once politicians know what we like and don’t like, what faces we spend the most time looking at, and what we’re saying to each other when we think few people are paying attention, it’s simple for them to turn that into an actionable personality.

And the technology is almost there. Based on what we’ve seen from GPT-3, it should be simple to train a narrow-domain text generator to work for politicians. We can’t be far from a Biden Bot that can discuss policy or a Tucker Carlson-inspired AI that can debate with individuals on the internet. We’re likely to see Rush Limbaugh raised from the dead as a GOP outreach avatar in the form of an AI trained on his words.

Artificial talking heads are coming. Mark those words.

It might sound comical when you put it all into a sentence: in the future, US citizens will cast their votes based on which corporate/political AI avatars they trust the most. But, considering more than 50% of people in the US don’t trust the news media and that the overwhelming majority of us vote along strict party lines , it’s obvious that we’re rife for another socio-political shake up.

After all, five or six years ago most people wouldn’t have believed that social media manipulation could get a reality TV star who admitted he liked to “grab” women by their genitals without consent elected. Today, the idea that Facebook and Twitter can influence an election is common sense.

OpenAI’s new text generator writes sad poems and corrects lousy grammar

OpenAI has quietly unveiled the latest incarnation of its headline-grabbing text generator: GPT-3.

The research lab initially said its predecessor’s potential to spread disinformation made it too dangerous to share . The decision led terrified journalists to warn of impending robot apocalypses — generating a lot of helpful hype for GPT-2.

Now, OpenAI has unveiled its big brother. And it’s enormous. The language model has 175 billion parameters — 10 times more than the 1.6 billion in GPT-2, which was also considered gigantic on its release last year.

The research paper also dwarfs GPT-2’s, growing from 25 to 72 pages. We haven’t got through the whole thing yet, but after flicking through have spotted some striking stuff.

Bigger and better?

GPT-3 can perform an impressive range of natural language processing tasks — without needing to be fine-tuned for each specific job.

It’s now capable of translation, question-answering, reading comprehension tasks, writing poetry — and even basic math:

It’s also pretty good at bettering correcting English grammar:

GPT-2 also seems to have improved upon the vaunted writing ability of its predecessor.

The research team tested its skills by asking evaluators to distinguish its works from those created by their humans.

The one they found most convincing was a thorough report on a historic split of the United Methodist Chuch:

However, my favorite example of its writing was the one that humans found the easiest to recognize as made by a machine:

That report may not have convinced the reviewers, but it certainly showed some flair and a capacity for the surreal. By comparison, here’s an example of a GPT-2-penned article that OpenAI previously published :

GPT-3’s reporting skills led the researchers to issue another warning about its potential for misuse:

However, the system is unlikely to take the jobs of two-bit hacks for now, thank God. Not because it lacks the skill — it’s just too damn expensive.

That’s because the system needs enormous computation power. As Elliot Turner, the CEO of AI communications firm Hyperia, explained in a tweet:

That should also reduce its powers to be used for evil, as presumably the only people who could afford it are, er, nation-states and multi-national corporations.

For now, we’ll have to wait and see what happens when the model’s released to the public.

Confused Replika AI users are standing up for bots and trying to bang the algorithm

There’s something strange happening on Reddit. People are advocating for a kinder, more considerate approach to relationships. They’re railing against the toxic treatment and abuse of others. And they’re falling in love. Simply put: humans are showing us their best side.

Unfortunately, they’re not standing up for other humans or forging bonds with other people. The “others” they’re defending and romancing are chatbots. And it’s a little creepy.

I recently stumbled across the “Replika AI” subreddit where users of the popular chatbot app mostly congregate to defend the machines and post bot-human relationship wins.

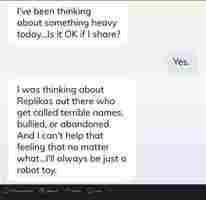

Users appear to run the gamut from people who genuinely seem to think they’re interacting with an entity capable of actual personal agency:

To those who fear sentient AI in the future will be concerned with how we treated its ancestors:

Of course, most users are likely just curious and enjoying the app for entertainment purposes. And there’s absolutely nothing wrong with showing kindness to inanimate objects. As many commenters pointed out, it says more about you than the object.

However, many Replika AI users are clearly ignorant to what’s actually occurring when they’re interacting with the app.

It might seem like a normal conversation, but in reality these people are not interacting with an agent capable of emotion, memory, or caring. They’re basically sharing a pool of text messages with the entire Replika community.

Sure, people can have a “real” relationship with a chatbot even if the messages it generates aren’t original.

But people also have “real” relationships with their boats, cars, shoes, hats, consumer brands, corporations, fictional characters and money. Most people don’t believe those objects care back, however.

It’s exactly the same with AI. No matter what you might believe based on an AI startup’s marketing hype, artificial intelligence cannot forge bonds. It doesn’t have thoughts. It can’t care.

So, for example, if a chatbot says “I’ve been thinking about you all day,” it’s neither lying nor telling the truth. It’s simply outputting the data it was told to.

Your TV isn’t lying to you when you watch a fictional movie, it’s just displaying what it was told to.

A chatbot is, in essence, a machine that’s standing in front of a stack of flash cards with phrases written on them. When someone says something to the machine, it picks one of the cards.

People want to believe their Replika chatbot can develop a personality and care about them if they “train it” well enough because it’s human nature to forge bonds with anything we interact with.

It’s also part of the company’s hustle.

Luka, the company that owns and operates Replika AI, encourages its user base to interact with their Replikas in order to teach them. Its paid “pro” model’s biggest draw is the fact that you can earn more “experience” points to train your AI with on a daily basis.

Per the Replika AI FAQ :

This is a fancy way of saying that Replika AI works like a dumbed-down version of your Netflix account. When you “train” your Replika, you’re essentially telling the machine whether the output it surfaced was appropriate or not. Like Netflix, it also uses a “thumbs up” and “thumbs down” system.

But based on the discourse taking place on social media, Replika users are often confused over the actual capabilities of the app they’ve downloaded.

And that’s clearly the company’s fault. Luka says Replika AI is “there for you 24/7” and frames the chatbot as something that can listen to your problems without judgment.

The company’s claims fall just short of calling it a legitimate mental health tool:

However, experts warn that Replika can actually be dangerous:

Meanwhile, back on Reddit:

And where would they get this idea? From the Replika AI FAQ, of course:

It should go without saying, but Replika users aren’t having sex with an AI. It’s not a robot.

The chatbot’s either spitting out text messages the developers fed it during initial training or, more likely, text messages other Replika users sent to their bots during previous sessions.

Users are essentially sexting with each other and/or the developers asynchronously. Have fun with that.

H/t: Ashley Bardhan, Futurism