My weekend without internet: A cautionary tale about the dangers of AI

I spent a weekend without internet and now I think humans will be extinct in 40 years. That’s not the sexiest lede I’ve ever written, but it is provocative. It shouldn’t be.

Most of us aren’t humans anyway. So, the idea that our few remaining homo-sapien ancestors will be the last of their kind shouldn’t surprise anyone.

Let me backtrack a bit before anyone confuses this with a conspiracy theory manifesto. If you’ve followed our newsletter ( click here ), you’ll know that here at Neural we like to call ourselves “cyborgs.”

This isn’t a vanity or marketing thing, it’s a statement of reality. People like us – the kind of person who’s always looking forward to the newest gadgets, absolutely loves the hard sciences, and thinks artificial intelligence is the future – are actual, living breathing cyborgs.

Sure, we’re not superhero human-machine hybrids like Robocop or the DC Comics character named Cyborg. But we are human-machine hybrids.

This has never been more evident to me than this past weekend, which I spent without internet. On Saturday, my local electric company replaced some power lines on my street and in doing so managed to sever the fiber cable coming into my home. It wasn’t repaired until Monday afternoon.

You might be thinking “oh, the horror,” but I’d like to assure you that me and my family were okay. We still had internet access through our phones so nobody was actually in danger of… missing out on a tweet or something.

I mean, haven’t we all gone without internet? This weekend, at first, was no big deal. I’ve got enough video games and movies to hold me over for months before I need to check back in with reality.

Social media isolation and boredom ended up being the least of my worries. As it turns out, there were some legitimately spooky side-effects to not having WiFi in my house over the weekend.

I had my phone, but without WiFi my connection was spotty and slow. I found myself frustrated over and over as I picked up my phone to do something trivial and realized it was going to take 20 seconds or so for my Search to go through or my bank account to load.

Again, I want to point out that I don’t actually care about using the internet. I’m a middle-aged dude, I spent most off my life “offline,” so my frustration wasn’t based in laziness or a petty “why won’t it work right!?” mentality.

I found myself having difficulty thinking. By Sunday evening I realized that I use the almost-instant connection I have with the internet to augment my mental abilities almost constantly.

I’ve stopped memorizing anything trivial. I don’t know what day the Battle of Hastings was fought because I have Google to know that for me. What I do know is that I’ve read half a dozen excellent articles about it while researching, and I believe I understand plenty about the battle without knowing offhand it was fought on 14 October, 1066.

And this evolution of my mind – or de-evolution, depending on your point of view – happened without me knowing it. I wasn’t aware of how much I rely on the AI-powered internet as a performance aid.

According to Pew research , 97% of people in the US own smartphones. We might not all use them the same way, and not everyone has high-speed internet access all the time, but we all face the same danger: over-reliance.

The more dependent we become on AI, the harder it’ll be to reconnect with our unaugmented roots should the need ever arise.

A weekend without high-speed internet access showed me just how much I rely on algorithms to help me think, as long as it’s near-instant and frictionless .

And, perhaps most noteworthy of all: I wasn’t raised on the internet like many people. I was born in the 1970s. I didn’t use the internet until I was 19. Tomorrow’s cyborgs will be even less like yesterday’s humans than I am.

If AI only had a brain: Is the human mind the best model to copy?

The Holy Grail of AI research is called “ general artificial intelligence ,” or GAI. A machine imbued with general intelligence would be capable of performing just about any task a typical adult human could.

The opposite of general AI is narrow AI – the kind we have today. For example, you can ask Alexa to do all sorts of stuff but when you try to get it to do something it’s not specifically designed for it fails.

A general AI, on the other hand, wouldn’t necessarily need to know how to do something before it tried.

The current technological mindset in the field of machine learning dictates we accomplish GAI through the development of classical neural networks that attempt to imitate the machinations of the human brain.

But what if that’s a dead-end? What if GAI continues to elude us for as long as we fail to completely understand the human brain ? Or what if there simply isn’t any way to replicate the human mind in a classical computer system?

Scientists know startlingly little about how the human mind works. You can see how divided researchers in the hard sciences are when it comes to understanding cognitive function by Googling “what is consciousness” and checking out the diversity of expert opinions on the matter.

Furthermore, it’s arguable that trying to translate human brain activity into a digital replication is a lot like trying to describe the beauty of a sunset using only pantomime.

And that’s because the human brain may actually be a quantum machine . To put it in obscenely simple terms, our brains may process information in ways that a binary system (a classical computer) simply cannot.

At the end of the day we could be barking up the wrong tree by trying to imitate an organic machine we don’t fully understand.

But, luckily for humanity and any future sentient machine lifeforms that may one day exist beside us, there are more brains out there than just ours. And it seems at least possible that, based on our current level of technology, some of them might make better blueprints for GAI.

Cuttlefish or future robot overlord?

New research out of the University of Cambridge in the UK indicates that these adorable marine mollusks have a major mental advantage over humans: they can remember what they ate for dinner last Tuesday.

Okay, that might not sound like a superpower but it’s actually quite impressive.

Per a Cambridge press release :

But, according to the peer-reviewed research, cuttlefish don’t have this problem. They suffer from many of the same aging problems as we do – muscle deterioration, loss of appetite, et cetera – but they apparently retain episodic memory even in the last few days before they die of old age.

This is because the cuttlefish brain doesn’t have a hippocampus.

Neuroscientists believe episodic memories are stored or accessed through the hippocampus, a big part of our brain we believe is responsible for all sorts of advanced mental processes.

The fact that cuttlefish retain and access those memories in old age without a hippocampus indicates there’s more than one way to accomplish neural feats – and that simpler models can outperform complex ones.

The cuttlefish is a fascinating creature capable of generating light shows, camouflaging itself, and communicating across numerous mediums. It’s widely considered the most intelligent invertebrate in existence today.

And there’s a whole planet full of other animal brains out there. Many of the Earth’s creatures are capable of mental feats human minds can barely fathom (let alone imitate).

In our current biological state, we’ll never know what the it feels like to sense the planet’s magnetism and navigate with pinpoint accuracy along thousands of kilometers relying on nothing but a sixth sense like many birds do . And our brains don’t contain the necessary systems to detect tiny fluctuations in the atmospheric electrical energy from kilometers away as sharks can.

There are sensory machinations, functions, and experiences that occur in other organic neural networks that we’re not anatomically capable of.

This isn’t to say that we should teach machines how to navigate by magnetic poles. The point is that nature takes many paths to accomplish a goal and the most complex one usually isn’t where things start.

An alligator is just as capable of navigating and surviving in a complex and changing environment as a modern deer is – but its tiny brain is millions of years less-evolved.

Maybe the most prudent path forward for GAI is to gain a complete functional knowledge of how the brain of a cuttlefish, shark, alligator or bird works.

Right now, organizations such as OpenAI that are focused on GAI seem to be attempting to button-mash the emergence of a human-level intellect by simply increasing a machine’s power and ability to run deep learning algorithms.

It’s unclear whether that’s a viable strategy at this point. We certainly don’t seem to be any closer to GAI today than we were five years ago, but there’s no timer here.

After all, it took nature millions of years to pull off human intelligence.

But we know for certain there’s at least one way to develop intelligence because of the fact it does exist in nature.

Perhaps it’s time the world’s AI researchers started working with animal brain specialists instead of wandering in the dark trying imitate the complexities of the human mind through brute force .

Researchers created a brain interface that can sing what a bird’s thinking

Researchers from the University of California San Diego recently built a machine learning system that predicts what a bird’s about to sing as they’re singing it.

The big idea here is real-time speech synthesis for vocal prosthesis. But the implications could go much further.

Up front: Birdsong is a complex form of communication that involves rhythm, pitch, and, most importantly, learned behaviors.

According to the researchers, teaching an AI to understand these songs is a valuable step in training systems that can replace biological human vocalizations:

But translating vocalizations in real-time is no easy challenge. Current state-of-the art systems are slow compared to our natural thought-to-speech patterns.

Think about it: cutting-edge natural language processing systems struggle to keep up with human thought.

When you interact with your Google Assistant or Alexa virtual assistant, there’s often a longer pause than you’d expect if you were talking to a real person. This is because the AI is processing your speech, determining what each word means in relation to its abilities, and then figuring out which packages or programs to access and deploy.

In the grand scheme, it’s amazing that these cloud-based systems work as fast as they do. But they’re still not good enough for the purpose of creating a seamless interface for non-vocal people to speak through at the speed of thought.

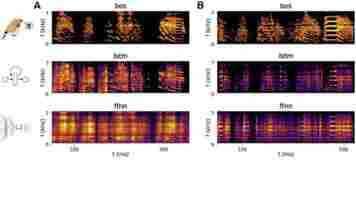

The work: First, the team implanted electrodes in a dozen bird brains (zebra finches, to be specific) and then started recording activity as the birds sang.

But it’s not enough just to train an AI to recognize neural activity as a bird sings – even a bird’s brain is far too complex to entirely map how communications work across its neurons.

So the researchers trained another system to reduce real-time songs down to recognizable patterns the AI can work with.

Quick take: This is pretty cool in that it does provide a solution to an outstanding problem. Processing birdsong in real-time is impressive and replicating these results with human speech would be a eureka moment.

But, this early work isn’t ready for primetime just yet. It appears to be a shoebox solution in that it’s not necessarily adaptable to other speech systems in its current iteration. In order to get it functioning fast enough, the researchers had to create a shortcut to speech analysis that might not work when you expand it beyond a bird’s vocabulary.

That being said, with further development this could be among the first giant technological leaps for brain computer interfaces since the deep learning renaissance of 2014.

Read the whole paper here .