Patently obvious – the iPhone 6S won't have these features

Covering the latest Apple iPhone rumours is always a slightly frustrating game. Alongside the general bits of information, there are spikes of interest around a newly-discovered patent, which make people clamour to the conclusion that the item featured will definitely be a feature of the iPhone 6S (or whatever the next upcoming product is). In most cases, the patent in question has nothing to do with the new phone and we're not getting any useful information from them; it tends to be that older patents are more useful as background information pointing out the possibility of a company going down a specific route.

That doesn't mean that patents are completely pointless, but it's worth understanding what they, what they're for and how companies like Apple use them. With plenty of legal cases between companies suing each other over alleged patent infringements, it's clear that the subject is big business and big news. Here we're looking into the slightly murky world of patents and patent law to find out what they're all about.

What is a patent?

A patent gives an inventor or company exclusive rights to a invention, for a limited time period in exchange for a full public disclosure. In the case of patents that period is generally 20 years. It's important to note that having a patent doesn't give a company a legal right to manufacture a product, but it does give it legal rights to prevent other companies from manufacturing or selling a patented invention. This can help one company gain a technological advantage over its competition, preventing them from doing the same thing, or it can be a money-spinner, with a patent licensed out for a fee. All patent cases are civil cases, rather than criminal ones.

How do you get a patent?

A patent must be applied for through a country's patent office, with worldwide treaties typically enforcing the patent across the globe. Register at the US Patent and Trademark Office , and the patent will be upheld in the UK. The application process differs slightly from country to country, but both individuals and companies can hold patents (in the US, the inventor has to apply, but can assign the patent to the company that they work for).

Interestingly, to file a patent, you don't have to have a working example of it in action in most countries. As the US Patent and Trademark Office explains: "An example may be 'working' or 'prophetic.' A working example is based on work actually performed. A prophetic example describes an embodiment of the invention based on predicted results rather than work actually conducted or results actually achieved."

What that means in practice is that a company can come up with designs or descriptions of how a system would work and, provided the results show that the device would work, a patent can be granted.

What can be patented?

A patent is for an invention that actually works, so you can't put in patent for a perpetual motion machine, as it's technically impossible to build. Company logos are also barred (these are Trademarks) as are works of art and literature, which come under copyright.

By invention, we mean that you can get a patent for a physical machine or the way that it's manufactured (a process). Note that 'process' also includes computer software. An invention must also be unique: it can't have been done before; patents don't even cover products that are similar to existing ones, so the new invention has to be substantially different. A product put forward for a patent has to also be useful, so you can't just get a patent for any old bit of tat.

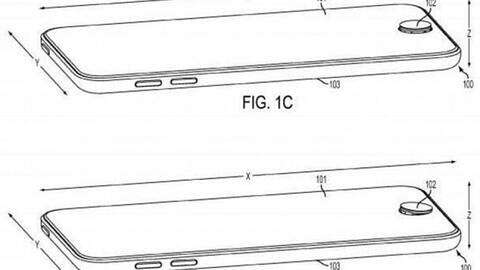

It's also possible to patent designs (design patents), and plants, which have been genetically created. You'll often find that technology companies have design patents to protect the look of their products and to try and prevent cheaper clones from being produced.

In all cases, note that the patent wording is deliberately very loose, to give as much scope for inventions as possible; it has the side effect of making legal cases extremely complicated as well.

What do companies patent?

In practice, companies will patent everything and anything that they can. As there's not a burden of creating a working example, it means that projects in early stages can be patented, provided the documentation shows that the product would work if it were built. Generally speaking, if someone at a company comes up with something new that looks useful, you can bet that the company will file it with the patent office.

When do patents have to be applied for?

A patent can be applied for provided that the invention hasn't been used publically, put on sale or described in a publication one year before the patent application date. In other words, a company has a year from selling a product to patent everything inside it. This means that a company, such as Apple, can secretly work on something, putting in a patent application at a later date. Of course, there is a risk with this strategy, as another company may independently arrive at the same invention and gain a patent first.

What do companies use patents for?

Patents are income and leverage in the technology world. Companies generally use them, as discussed at the start of this article to stop the competition from doing something similar, or for generating income. Patents are also useful in legal action: if you're getting sued for using a competitor's patent, but they're using one of yours, you can use that as leverage for a settlement. This kind of action means that patents are very valuable; in fact, companies are often bought because of the range of patents that they hold. Recently, when Google sold Motorola to Lenovo it kept hold of the patents it had acquired, some of which will be used in the Android operating system.

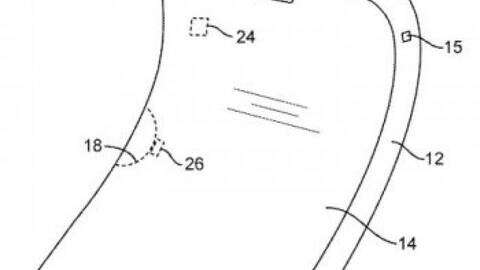

Having a massive portfolio of patents is seen as a good thing for most companies, but it's important to realise that just because a patent has been granted, it doesn't mean that a company has to use it. For example, Apple recently got a patent for a home button that can pop-out into a joystick and be used as a games controller. As clever an idea as this is, it doesn't mean that it's going to be used in the iPhone 6S. Aside from adding complexity to the phone, there's a good chance that such an item would be prone to damage, getting stuck in people's pockets, for example. However, as a good idea, Apple has created the patent, so that it has protection if it decides to use this invention in the future, or the ability to sue someone else if they try and use it without the company's permission.

Other granted patents may prove too expensive for a company to put into production, or they may find that it doesn’t add the features they want to a product. Many of these patents are very forward-looking and you may not see final products for years, if at all.

In many cases patents are there for a company to use at its leisure, giving it the opportunity to do something in the future if it sees fit.

Doesn't patent law create the potential for abuse?

Without a shadow of a doubt. The fact that you don't need to have a working example in order to get a patent means that companies can basically register a bunch of patents that they have no intention of using and then sue other companies for breach of patent laws. There are even patent trolls, who create or acquire patents and then scour the world looking for people who are using the technology and sue them.

There's also a good argument that you shouldn't be able to patent software. Software, eventually, is compiled down to machine code, which runs on a processor. As such, it just asks the CPU to run certain commands, which can be seen as not really an invention; it would be like owning a patent on putting a series of words together. It's too big a subject to get into here, but software copyrights, some believe, destroy innovation and remove competitiveness.

Can anyone do anything against patents?

Although the granting of a patent is fairly straightforward, they're not completely water-tight and when court cases come up, patents can get thrown out. For example, Apple had a design patent covering the iPad's shape: a rectangle with rounded corners. In a court case Apple brought, Samsung was found to have breached several patents, but the jury ruled that you couldn't have a design patent on a geometric shape, which makes perfect sense.

Generally, when one company is sued by another, the defence team often goes out looking for 'prior art'. That is, an existing product that proves that the invention in the patent is already known. If this can be proved, then the original patent is no longer valid. There are other defences, too, but the big problem is that these kinds of cases cost a lot of money.

What can we learn from this?

The big takeaway is that a patent is not an intention to produce a product, and companies don’t like advertising what they’re up too. Every time you see a patent story, you should treat it with a big old handful of salt. It’s fair to say that the patent system, in its current guise, brings up plenty of issues for companies and can be said to stifle innovation. That’s not to say that they should be scratched, but many people would welcome change.