Scientists may have discovered a way to make us forget bad memories

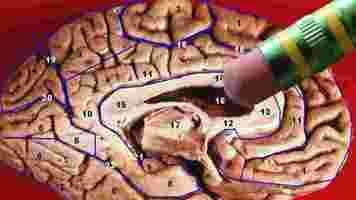

Researchers at Cambridge University have discovered a protein in the brain of mice that may act as a biomarker for malleable memories. In other words, they may be able to determine which memories we can erase and which we are, for whatever reason, stuck with.

Up front: The researchers conditioned laboratory mice by simultaneously shocking them and making a clicking noise. The mice naturally associated the sound with the shock and, thus, developed a fear response. Because the mice remembered being shocked, they associated the noise with discomfort.

The researchers then injected the mice with propranolol, a beta-blocker, and the results were shocking: nothing happened. The mice should have gained amnesia and forgotten the association between the clicking noise and being shocked, but they didn’t.

Background: Previous research on inducing amnesia in laboratory rats has shown that propranolol was effective. This time around, however, the Cambridge researchers discovered the presence of a specific protein in the neurons they expected to be affected.

Per a university press release :

A bit deeper: The researchers now know why propranolol doesn’t always work. But they don’t know why the shank protein stops it or even why it’s there sometimes and not there other times.

Like all great research, this study answers some questions but asks even more.

The important thing is that, with further research, these findings could have huge implications for humans.

The researchers are quick to point out that this isn’t the stuff of science fiction. I t’s unlikely you’ll be able to go full Men In Black and zap someone’s memory in a targeted manner.

The discovery of this biomarker may lead to some incredible findings in our ability to treat conditions such as PTSD or to help people forget subconcious trauma.

Lead researcher Amy Milton, per a university press release, said:

Quick take: We don’t know much about how organic memory works. Conditions such as Alzheimer’s and dementia remain uncured due to the complexity of the human brain and the challenges involved in interpreting its machinations.

Finding a biomarker that we can associate with memory, even in a mouse’s brain, is a giant step forward in our understanding even the most basic memory functions.

This could lead to chemical treatments to effectively cure emotional trauma.

As far as we can tell, however, the team hasn’t released a research paper. The research is currently tagged as “non peer reviewed” on EurekAlert. That doesn’t mean it isn’t a strong study (this is Cambridge we’re talking about). But it does mean we should take it all with a grain of salt until peer-review replicates the findings.

You’re wrong about the metaverse

Baseball’s back and I couldn’t care less. What I’m excited about is the world champion Atlanta Braves’ new virtual stadium.

A company called Surreal Events is working with the champs to bring a virtual representation of Truist Park to life via a virtual platform-as-a-service model built in the Unreal engine.

As boring as that sounds, the emergence of an interface-agnostic portal to bespoke metaverses might be what finally convinces the cynical masses that the future is now.

It’s not so much that a digital ballpark exists, it’s what it represents.

Surreal Events invited me to a demo of their browser-based metaverse streaming service where I got hands-on with the platform via good old-fashioned keyboard and mouse.

I’m all-in on metaverse technology, but only because I’m willing to strip away all the dumb crap surrounding the idea and view it for its potential.

The first problem most people have with the metaverse is virtual reality. And it was immediately clear that Surreal’s technology solves that problem.

I love VR. I could spend half an hour grinning at the 3D grid you exist in while a SteamVR experience loads. I’ve reviewed dozens of VR games and experiences and I currently own five different headsets.

That’s why I was shocked to experience VR sickness for the first time a couple years ago. I figured you were either among the small percentage of people who get sick in VR or you weren’t. But, as it turns out, everyone can get VR sickness.

That alone makes it a crappy platform for anything that’s supposed to have wide appeal. If playing Candy Crush or Farmville made a significant portion of the population vomit at random intervals, Facebook /Meta might not be the technology juggernaut it is today.

The fact of the matter is that Meta, Microsoft, and a dozen other companies are trying to position the metaverse as a place where business happens.

And that means there’s a zero-percent chance that the metaverse will succeed in a VR-only format. Luckily, it doesn’t have to.

Instead, just like you can still use Zoom even if you don’t have a webcam, you’ll almost certainly be able to experience most of what the metaverse has to offer without dipping a single toe into virtual reality.

During my Surreal demo, I checked out indoor showrooms, meeting rooms, and outdoor social venues. The graphics were crisp and never once lagged. And there were no stutters or glitches during voice chat despite the fact I was streaming audio in-browser for the demo and for a separate video chat with the team.

I also never needed a tutorial or help with the controls. The user interface was dead-simple and anyone who’s ever used “WASD” controls or arrow keys to move an object on a screen can navigate the virtual world.

Everything just worked. I went from clicking the link in my email to creating my avatar in a matter of seconds.

This makes the metaverse as accessible as a YouTube video or PC game, making anti-VR arguments against it moot. It also addresses the second big problem the platform has: the general public’s misconceptions on metaverse commodification.

The idea that the metaverse is just a giant SkyMall for VR nerds to buy digital collectibles is a bit silly.

Sure, there’ll be all manner of stupid crap to buy in the metaverse, but that’s no different than the real world or the internet.

Digital Truist Park, for example, probably won’t be selling unique hotdog NFTs at its virtual concession stands. But, there’s a good chance you’ll be able to interact with a link to the club’s gift shop and online ticketing agent while you’re logged in.

In the future, we’ll watch as virtual spaces grow and evolve. So, for example, your favorite band might host their own metaverse space that fills up with mementos from albums and tours over the years.

Those spaces could act as conduits to other spaces within a record label’s influence, or connect to a hive-like network including millions of other bands. The ability to transfer preferences, settings, commodities, avatars, and a record of your experiences from one entity to another, or even from one platform to another, will be what separates the metaverse from the classic internet or bespoke gamified environments such as Second Life.

But it only works if the metaverse is as easy to access as social media. My brief experiences in the Surreal Events demo showed me this is possible.

Wake up sheeple: AI shows all tourists basically take the same picture

Images shared online have a big impact on how we travel. As documentary photographer Sara Melotti puts it :

Sad as it may be, those photos can reveal a lot about our travel choices, as Facebook‘s AI team recently discovered.

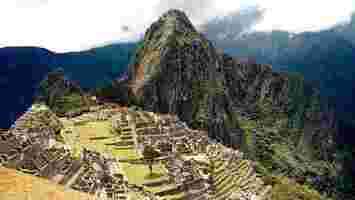

The researchers analyzed the influence that online photos and conservation policies have on travel patterns by applying algorithms to thousands of images of Cuzco, Peru.

The region contains a vast array of heritage sites, including the sprawling citadel of Machu Pichu, the largest tourist attraction in the country. But its ancient Inca treasures weren’t built for millions of travelers, which has led Peruvian authorities to introduce a range of conservation initiatives that restrict tourist movements.

The researchers assessed their impact by studying 57,804 Flickr photos taken at 12 different sites in Cuzco. The images were geotagged and given timestamps spanning from 2004 to 2019 to help the AI work out how travel choices in the region have changed over time.

The team then analyzed the dataset with computer vision and machine learning algorithms to understand how tourists move across the region.

The most popular attraction was, unsurprisingly, Machu Pichu, followed by the ancient Incan capital of Cuzco, the main entry point to the region. The least popular were the ruins of Pikillacta and Tipón, which is understandable given to their remote locations.

Tourists spent the longest time at Cuzco, the region’s only transportation hub and the location of most of its hotels and guesthouses. The most frequent transitions between sites were from Tambomachay to Puca Pucara — which are only a three-minute walk apart — and towards Machu Picchu.

Changing tourist movements

The researchers then looked at how restrictions on visitor numbers and movements had impacted the photos. The results suggest the conservation initiatives are working — but also making tourist photos more generic.

The introduction of predefined routes through heritage attractions had increased the photo homogeneity at Cuzco’s big attractions. At smaller sites where tourist movements are unrestricted, the photos remained more varied.

Next, the team examined how tourists photograph these attractions. All the sites featured an abundance of mountain landscapes, alpaca, and stone architecture.

Images of Peruvians wearing traditional dress were mostly found in Cuzco, Chinchero, and Pisac. All these sites host large open-air markets for souvenir shopping, while Cuzco also many festivals and parades where traditional dance groups perform. Colonial architecture was also a popular subject for photographers, particularly in Cuzco and Chinchero, where colonial churches are a major tourist attraction.

Finally, the researchers investigated how historical images influence contemporary tourism. Notably, many of the recent images were similar to photos taken by explorer Hiram Bingham, whose expeditions to Cuzco in the early 19th-century helped popularize the region as a tourist destination.

The team believes the techniques can offer vital information about heritage conservation and the management of archaeological sites. They could also help identify emerging travel hotspots, and which destinations are no longer attracting the focus of our cameras.